Danceletter 24

Back when going to the gym was something you could do in New York City, I would sometimes drag myself to the local YMCA, then come home and tell my boyfriend how glad I was I went. He would say, “No one ever regrets working out,” which I think is funny (and true). This crossed my mind today when I found myself almost backing out of the online “dance experience” I had signed up for earlier this week, Sunday Service, a joy-filled class with Bay Area dancer, choreographer, and astrologer Larry Arrington (which I wrote a little bit about here). I won’t take you through all the reasons I might avoid doing something that would obviously be good for me. I’ll just cut to where you probably know this is going: I showed up for Sunday Service, and I did not regret it.

I’ve had varying experiences with online dance classes. I actually haven’t taken too many, sometimes preferring to do my own thing (or nothing at all). Early on in stay-at-home life, a friend and I agreed to simultaneously attend Dance Church® Go, an online version of the popular improvisational dance-fitness class known as Dance Church®. I lasted about 15 minutes. My WiFi connection was shaky, and on that particular night, trying to simulate a live experience over the internet, under the pressure-to-feel-happy of so many pop songs, only made me more depressed. This isn’t to say you shouldn’t try Dance Church® Go, or that I won’t try again; it just didn’t work for me at that time.

One thing I appreciate about Larry’s class, in addition to the good vibes she showers upon us, is that she acknowledges how bizarre it is to be dancing together on Zoom, while also making the best of the remote situation. Like, we all know this isn’t ideal and not the same as gathering in person. With that out in the open, I find it easier to accept and even enjoy the awkwardness of bopping around alone in my living room, in time (more or less) with dozens of strangers bopping around in theirs. Larry is also not at all concerned with people doing the choreography “right,” which, as someone who has always been slow to pick up steps, I find liberating. The emphasis is more on just moving, moving, moving. And sweating, a lot. And — she doesn’t say this, but she does make room for it — having a good cry if you need to. (I did during one combo today.)

At this point much has been written about the pandemic-era phenomenon of online dance classes and, more broadly, learning choreography from screens. While I was writing this, I happened to check Twitter (as one does when one can’t decide what to say next) and came across this lovely, looping meditation by Michaela Dwyer — with images by her sister, Sarah Dwyer — on the transmission of movement from one body to another, whether in person or through film or social media. (“David Byrne’s hips onstage are a wronged metronome”: an observation gleaned in part from YouTube. “Dear Personal Practice on Instagram, It is very hard to learn your choreography.”)

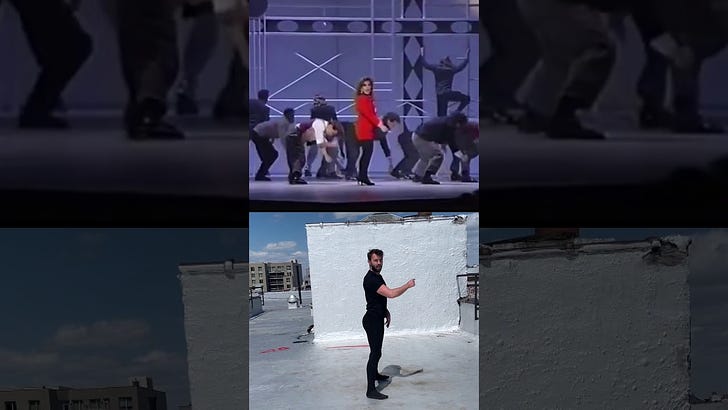

Along similar lines, Rennie McDougall writes in The Brooklyn Rail about learning, in the confines of his apartment, some of Paula Abdul’s choreography from the 1990 American Music Awards. Apparently Abdul would choreograph just after waking up in the morning, and in his lovingly painstaking reconstruction, Rennie even honored the drowsiness of her process. A nice #dancedreams intersection here:

Abdul said the choreography for the 1990 American Music Awards performance came to her in her sleep: “Almost all my choreography had to do with things that I would remember from my dreams, or I’d actually wake up and immediately write it down,” she said. “I used to have a tripod and a camera and I would videotape me half-asleep, just getting the ideas down so I wouldn’t forget.” This is how I started learning the dance, first thing in the morning and half-asleep having just woken up, still in whatever clothing I’d fallen asleep in the night before.

Here are the results, which Abdul herself has endorsed: